Continuous delivery of a Python library with AngularJS commit convention¶

I got tired of having to manually build and upload my library (Mountepy) to PyPI, so I decided to do what any sane programmer would do - set up automation [1]. But how would my scripts know whether they need to just update the README on PyPI and when to assemble and push a new version of the library? Thanks to the AngularJS commit convention! Oh, and Snap CI will run the whole thing. Why Snap, you ask? See my previous article - Choosing a CI service for your open-source project.

EDIT (2021-12-30)

I haven’t used the technique described here for a few years now. I or other team members would forget to prefix the commit messages correctly at times, which then required fixing the commits on origin (by force push). And that causes pull issues for other people.

I do think automatic version inference based on some commit classification is a good idea, but the source data should be kept in the repo. Maybe in release note files from towncrier.

Motivation¶

Let’s say that you have a Python library and that you follow semantic versioning. Let’s also assume that when your tests pass you have sufficient certainty that your software is ready for release (and you should have it) and you don’t require any pre-releases, beta versions or whatever. I’m sure it’s easier said than done for those important projects that many people depend upon, but it has to be doable.

If you introduce a change to the code you probably want to ship it to PyPI. When you’re introducing a fix or implementing a new feature it’s quite straightforward - you bump the version, create new artifacts (probably a wheel and a source archive) and then you push to PyPI.

But what if you only refactored a few tests? Then you don’t need to put anything on PyPI. And when you updated the readme or docs? The version shouldn’t change (it’s still exactly the same library as before the commit) but your documentation site (e.g. the project’s page on PyPI) needs to be updated. If you don’t care about any sane versioning (please, care), you could just create a new version of the library for every commit, but otherwise you need to be able to distinguish between the commits that affect the production code and those that don’t [2].

This is where AngularJS commit convention helps out. It’s originally meant for automatic changelog generation, but in essence it allows to distinguish between types of commits. It requires some work on the human part, of course, but I think that this work is not much more then the good practice of doing commits that are about a single change.

The build pipeline¶

SnapCI build setup¶

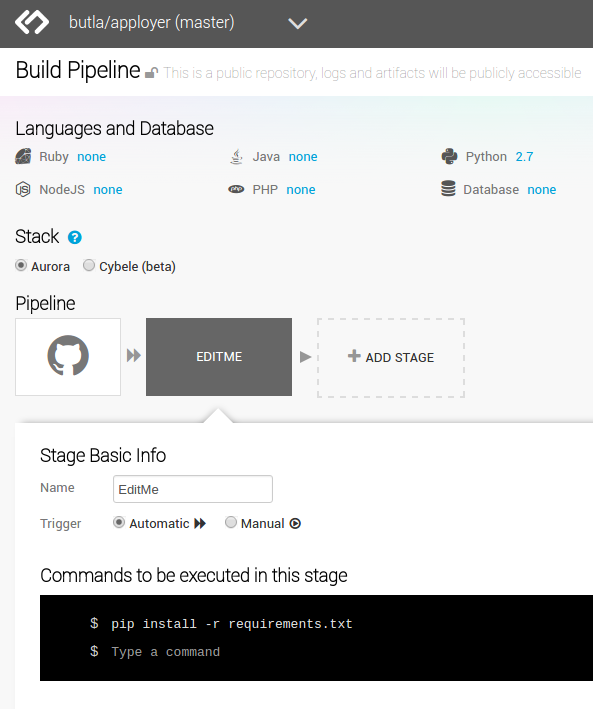

It’s straightforward to add a build configuration for any of your GitHub repositories in Snap, so I won’t go into it. When you add it you are sent to a page that looks like the one below.

You can change the version of Python in “Languages and Database”, you could even pick a different

technology stack, like NodeJS.

You may notice that you can only pick one language, but fear not if you need a mixed environment!

Additional (language) packages can simply be installed with yum

(as mentioned in Snap CI FAQ) in “Commands to be executed in this stage”.

About that commands section - it’s one of the best things about Snap in my opinion. You simply type in shell commands that you want to run for the given stage, and that’s it! As familiar and flexible a setup method as you can get.

Real-life tests stage¶

What you probably want to do in every CI is to build the code and run the tests. Most Python libraries don’t have to build anything, so just running the tests is enough, and this is what I did in the first stage of my build, uninspiredly named “TESTS” [3] (I’ve just renamed the default EDITME):

pip install tox # install Tox

tox # run it

Outside of running the tests and measuring test coverage my Tox setup does other things to check if the code is OK, and you’ll see that later.

The stage could end right there, but I also want to upload the coverage data gathered during tests to Coveralls to get that sweet 100% coverage badge on GitHub [4]:

pip install tox

tox

pip install coveralls

coveralls

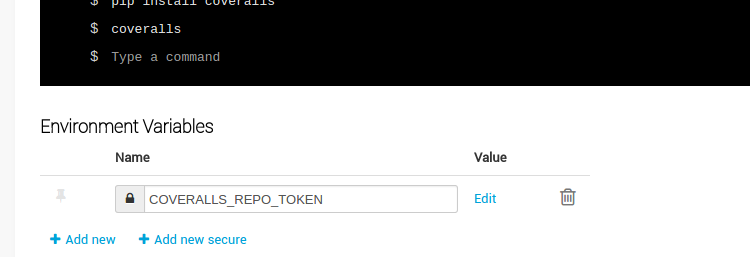

For Coveralls to work, it needs to have the repo token allowing it to upload data to your profile.

It will look for it in COVERALLS_REPO_TOKEN environment variable.

Thankfully, Snap allows to set secure (secret) variables that will be cut out of the logs.

Parsing AngularJS-style commits¶

As I’ve mentioned at the start of this article a commit message convention can be used to distinguish different kinds of commits and react to them properly (deploy a new version? update docs? do nothing?). AngularJS commit convention dictate that the messages look like this:

<type>(<scope>): <subject>

<BLANK LINE>

<body>

<BLANK LINE>

<footer>

So, for example (from Mountepy):

docs(README): Measuring coverage in mountepy tests

Also pointed to PyDAS for examples.

The available commit types and their meanings:

feat - new feature (hopefully with tests)

fix - a bug fix (also hopefully with tests)

docs - documentation

style - formatting, missing semi colons, etc.

refactor - some refactoring, optimization, etc.

test - adding missing tests

chore - project maintenance like build scripts, small tools, etc.

I’ve created a script (get_commit_action.sh) that can identify the commit type and dictate

the action that should be taken (by printing it):

#!/bin/bash

# If some command in this script fails then the commit was probably

# malformed and an error code should be returned.

set -e

# Taking the summary (first line) of the last commit's message.

COMMIT_SUMMARY=$(git log -1 --format=%s)

# Type of the commit is located before the mandatory parens

# explaining location of the change.

COMMIT_TYPE=$(echo $COMMIT_SUMMARY | cut -d "(" -f 1)

case $COMMIT_TYPE in

# These commits change the library code,

# so they must result in a new release.

feat|fix|refactor|perf) printf build_code;;

# Here, the actual library code isn't changed, so a new

# library version can't be released. But if we host the docs

# somewhere (library's README page on PyPI also counts),

# we should rebuild and upload them.

# Also, documentation updates sometimes go on the same commit

# with other minor tweaks, so we should (and don't risk

# anything by) re-release the docs just to be sure.

docs|style|test|chore) printf build_docs;;

# If the type isn't recognized,

# we raise an error and print to the error stream.

*) >&2 echo "Invalid commit format! Use AngularJS convention."; exit 2;

esac

Automatic deployment to PyPI¶

So let’s say that I’m using AngularJS commit convention and have the script to identify them. Now comes the part we’ve been waiting for - actually publishing (deployment of) the library to PyPI. The script to do that looks like this:

#!/bin/bash

set -ev

# Running the previous script to decide if we'll be uploading

# a new version or just updating the docs.

COMMIT_ACTION_SCRIPT=$(dirname $0)/get_commit_action.sh

COMMIT_ACTION=$($COMMIT_ACTION_SCRIPT)

if [ $COMMIT_ACTION == build_code ]; then

# Building source and binary distributions to upload later on,

# and setting the action that will be performed by Twine (PyPI

# upload tool) later in the script.

python3 setup.py sdist bdist_wheel

TWINE_ACTION=upload

else

# Only building the source distribution to update the package

# description on PyPI.

# If I had documentation on readthedocs.org I would rebuild it

# here. Sadly, I don't have it (yet).

python3 setup.py sdist

TWINE_ACTION=register

fi

# The file that contains repositories' configuration for Twine.

# For me, it points to the official and test PyPI

# This script's first argument specifies which one to use.

PYPIRC=$(dirname $0)/pypirc

# Depending on the commit type this will either upload the

# distribution files (upload) or update the package's metadata

# (register).

# PYPI_PASSWORD will be stored in a secure environment variable in

# Snap, like the Coveralls token.

twine $TWINE_ACTION -r $1 -p $PYPI_PASSWORD --config-file $PYPIRC dist/*

One thing to note about uploading a new version of the library: if the version number in setup.py isn’t incremented, then it will fail, because files on PyPI can’t be overwritten. A human is needed to change the version because we’re using semantic versioning. And if said human forgets to do that when he should (though I’ve created a script to help him remember), he can fix the CI build with a “fix” type commit bumping the version.

But you can say that, since we can automatically understand commit types, a machine

could increment the last version number (patch) on “fix”, “refactor”, and “perf”

commits, and the second version number (minor) on “feat”.

I won’t do that, because I have bad experience with automatic commits made by CI [5].

I think that the commit log starts to look ugly and gets twice as long with

a version-bumping commit done after every normal one.

A crazy idea once popped into my head to make the CI just amend the bumped

version onto the last commit to make the log look nicer, but it would force a developer

to pull --rebase after each push to origin, so it’s… crazy.

Finally, the step that uses the above script in my Snap setup looks like this:

pip install twine

# pypitest is a label in pypirc file with URL of,

# you've guessed it, test PyPI.

pypi_upload.sh pypitest

Why do I interact with test PyPI and not the real one? Well, to test stuff… I dunno. I can check if the files really get there, whether the README looks OK, etc. And only after that I trigger (manually) the next and last pipeline step:

pip install twine

# This time uploading/registering with the real PyPI.

# I've also got a different $PYPI_PASSWORD, an approach I recommend.

# You can store the passwords in KeePass, or something.

pypi_upload.sh pypi

Triggering a pipeline step manually can also come in handy when your code needs to go through some out-of-band (out-of-Snap) checks, like Windows tests on AppVeyor or some legal mumbo-jumbo before you can release the next iteration.

A bit of a warning - if you rerun the step or the whole build that successfully uploaded some artifacts, then it’ll fail, due to file collision on PyPI. I don’t see any real need to rerun them, though.

When introducing all of this to Mountepy I’ve put the CI scripts in another repository at attached them as a Git submodule to be able to reuse them in other projects and develop them independently.

Trunk-based development¶

You could have spotted a potential problem in my commit identification scripts: they only look at the last commit. But it’s normal to push more than one commit at once when you finish a bigger feature, right? Well, not according to trunk-based development, an approach suggested when trying to do continuous delivery or deployment.

I do recommend following the link, but if you don’t want to, the gist of trunk-based development is cutting the work up in self-contained commits and constantly synchronizing with master. The commit doesn’t need to provide a full fix or a feature, but it can be a step towards doing those. The important thing is that the commit doesn’t break anything and improves something. It could be a small refactor of one class on the road for implementing something.

I do think that this is the right way and it so happens that it’s also convenient for my automation.

But isn’t it too easy to break stuff when pumping everything into master? Especially if there are many contributors involved [6]? Well, not if you have good tests (and do other things mentioned in the Thought Works article).

In addition to running tests, my Tox config checks if the last commit is well formed and if the library’s version was bumped when it should be. With that, running Tox after creating a commit and before push should ensure [7] that we didn’t break anything and that a new version will be released if it’s needed. Of course, a human can even forget to run Tox before pushing… Well, git hooks or a development process requiring creating pull requests (Snap can run pipelines on them) can help with that.

Conclusions¶

I hope that you’ll find something inspiring in this article.

For me, continuous delivery (and deployment, where applicable) seems to be the way to go for software development on projects of every size. It allows to focus more on creative work (writing code) and less on things that are quite joyless (packaging, deploying, synchronizing releases, resolving merge conflicts, etc.). I should probably get around to reading the continuous delivery book…

Feel free to leave a comment if you see some issues with my setup or have improvements in mind.

Oh, and you can see my pipeline at https://snap-ci.com/butla/mountepy/branch/master

Footnotes